#91: Reflections on PD Design

- Wen Xin Ng

- May 23, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Nov 22, 2025

Over the past semester, I’ve had the privilege of working alongside educators in a number of teacher PD workshops—each one a unique opportunity to think about what it really means to design PD that matters. While I’ve always approached these sessions with a deep belief in the power of sound curriculum design and the importance of grounding tech in pedagogy, I’ve come away with a sharper clarity on how to design for impact.

Grounding the session in sound pedagogy before rethinking lesson design to ensure constructive alignment and alignment to DI principles.

What We’ve Done: A Look Back at This Semester

I started the semester with what I thought was a fairly clear approach: show what’s possible, excite people with the tools in SLS that can enable the transformation of T&L, and hopefully spark change. And to be fair, that worked—to an extent.

In designing the SLS module to show a school's KP team the possibilities of SLS in supporting synchronous lessons, I intentionally embedded teacher-facing “thought bubbles” throughout the module. These served as pedagogical signposts—surfacing the design rationale behind each activity, such as where assessment for learning (AfL) was embedded, or how the sequence supported constructive alignment.

Teachers experienced the lesson from a student’s perspective, which allowed them to feel the power of seamless, well-scaffolded design—polls activating prior knowledge, AI-enabled tools such as Learning Assistant (LEA) scaffolding thinking and Data Assistant (DAT) surfacing class trends. The hope was that, by experiencing good design firsthand, they wouldn’t just be told what effective use of tech looks like—they would live it. And in doing so, begin to imagine how they might adapt similar strategies for their own classrooms.

Summary of participants' reflections, courtesy of Data Assistant

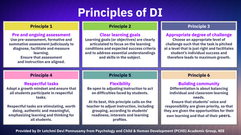

At the E3 Humanities Workshop, the focus was on exploring design principles—how purposeful lesson design can support Assessment for Learning (AfL) and Differentiated Instruction (DI), and how SLS can be a powerful enabler in this process.

Through a station rotation model, teachers experienced a variety of SLS tools in action and explored how each could support different pedagogical moves. More than just a showcase, the session created space for teachers to try out the tools hands-on and reflect on how they might meaningfully apply them in their own Humanities classrooms. By anchoring the experience in good design, we modelled how SLS can support active learning, timely feedback and learner-centred differentiation—when used with intentionality.

Exploring the affordances of AI-enabled tools in SLS through hands-on and discussion.

The E5 Geography EdTech Consultancy provided teachers with a space for levelling up lesson design by tapping into the affordances of SLS’ AI-enabled tools. We explored how features like the Learning Assistant (LEA) can promote student thinking, and how the Adaptive Learning System (ALS)enable self-directed learning when used purposefully.

The session centred on how SLS can scaffold understanding, personalise feedback, and nurture learner autonomy within thoughtfully designed learning experiences.

At the Sec Geography Curriculum Leaders’ Meeting, I had the opportunity to share about the Adaptive Learning System (ALS) and the enhancements introduced in the SLS March update. During the breakout session, we explored the integration of SLS' AI-enabled features into the Interactive Digital Textbooks to enhance Geography teaching and learning.

One of the features highlighted was the Annotated Feedback Assistant (AFA), which teachers found especially useful for marking essay questions. Shoutout to my AIEd colleagues who showed me how using custom prompts with AFA can enhance the quality of feedback—making it more targeted and aligned with what teachers typically look for when grading.

Rethinking Design: Insights and Areas for Growth

In designing PD, I’m mindful of the importance of aligning design with teacher needs. Many teachers have shared how they don’t know where to start when it comes to using SLS. So, I scoped the sessions intentionally—framing them around practical entry points and showing how each tool can support their subject teaching or even ease certain processes, and always within a sound pedagogical frame.

In doing so, I often assumed that seeing would lead to doing, and that doing would naturally lead to understanding. That if teachers experienced well-designed activities, they would be able to intuit the underlying principles and apply them in their own contexts. But experience alone isn’t always enough to prompt deep learning or sustained change. And while I do communicate the thinking behind the design, I tend to explain it upfront. This can short-circuit the learning process, resulting in missed opportunities for teachers to actively engage with the “why” behind the design choices. A more powerful experience might come from guiding them to uncover these ideas themselves through structured reflection, discussion, or critique.

This is something I’ve been reflecting on more deeply. Good design isn’t just something to be experienced—it should also empower. Good PD empowers teachers to think critically, make meaning, and adapt ideas for their own contexts.

I’m now learning to be more intentional about designing for transfer, not just awareness—so that teachers leave not just with ideas, but with the confidence and clarity to apply them purposefully.

Towards Better PD: Designing for Impact

Formulating Clear Success Criteria

One key shift I’ve made is recognising the need to anchor each PD session with a clearly articulated end goal. It’s not enough for participants to be aware of a tool or approach—what matters is what they are actually able to do with it afterwards. Ultimately, the guiding question is: What is to be done after the session?

For example, when I introduced Learning Assistant (LEA) to a group of teachers, I was clear in my own mind about its pedagogical affordance, i.e. scaffolding argumentation, supporting evidence-based reasoning. I also spelled out the guardrails: the ability to limit interactions to prevent over-reliance on AI, how the tool avoids giving straight answers to prompt student thinking, etc. So yes, maybe they walked away understanding that LEA is more pedagogically sound than other AI chatbots in the market. But I started to wonder—if I hadn’t spelled all that out, would the teachers have arrived at those conclusions themselves? And would they be able to apply the same lens to evaluate another tool on their own? I’m not sure.

It made me realise how crucial it is to have success criteria built into every PD session. Otherwise, it risks becoming a “feel-good” experience—I may perceive the session as effective based on engagement or Service Quality ratings, without really knowing if meaningful learning took place.

Now, I try to begin with the outcome in mind and ask myself: What change in thinking or practice do I hope to see? What does success look like? Success criteria are essential—not just for me as the facilitator, but for the teachers themselves. They need to know what they’re working towards. When we clearly define what success looks like (e.g. “I can evaluate the pedagogical soundness of an AI tool for my subject” or “I can design an SLS activity that enables AfL”), the learning becomes more focused, and teachers can better track their own growth.

Learner Centricity: Meeting Teachers Where They Are

Just as we design student learning to be learner-centric, PD should follow the same principle. That means resisting the tendency to run PD sessions in neat, sequential phases, and instead, starting where teachers are ready to begin. Sometimes, that means jumping straight into evaluating the quality of student learning. And often, it’s only when teachers see that their current design isn’t working that they’re compelled to rethink, refine, and iterate based on the intended learning outcomes.

Million dollar slides from Grandmaster

This approach isn’t just practical—it’s ethical. Referencing Balkan & Kalbag’s Ethical Hierarchy of Needs, we’re reminded that truly respectful design considers three key dimensions:

Respecting human rights: student/teacher inclusion, autonomy, transparency and safety

Respecting human effort (i.e. usability): student/teacher workload, flexibility, support

Respecting human experience: teaching/learning environment & culture, student/teacher motivation, affirmation, happiness, well-being and meaningful relationships

Applied to PD, this means ensuring that sessions are accessible and safe spaces for learning, mindful of teacher workload, and built to affirm and energise—not overwhelm.

It was through the NLCs I’ve been supporting that I witness this first-hand. The most powerful shifts didn’t happen during the lesson design presentations or walkthroughs—it happened when teachers were asked to design, enact and share. It was through getting their hands dirty and engaging with real lesson artefacts that sparked authentic conversation, critical reflection, and ultimately, growth. And to me, that’s what respectful PD design looks like.

None of this work happens in isolation. I’m grateful to my colleagues, especially the Geography Master Teachers, who consistently keep pedagogy at the heart of every conversation. Each interaction with the MTTs helped sharpen my thinking and ground my ideas in sound practice. I really appreciate the way they engage deeply, supportively, and always with genuine curiosity—whether it’s bouncing around ideas or exploring new areas like gamification.

What I’m appreciating more and more is that meaningful PD isn’t just about showing what’s possible. It’s about helping teachers connect with the why, see the how, and try the what for themselves. And just like we do with our students, we need to create space for teachers to reflect, iterate, and grow in their own time and context.

Feeling energised to continue pushing new boundaries with the Geography fraternity!

Comments